Transracial Adoption Concerns are Warranted and Beyond Amy Coney Barrett

In recent days there have been accusations of a political “witch hunt” attacking Supreme Court nominee Amy Coney Barrett’s with “repulsive” comments about her adoptions from Haiti. These claims are a red herring intended to dismiss the very real and warranted apprehensions about transnational and transracial adoptions that have existed long before the current nomination and reach far beyond the scope of any single adoption or individual adopter.

Transnational aka intercountry, aka international adoption (IA), is notoriously fraught with corruption, kidnapping, trafficking, and exploitation of poverty, war, political unrest and natural disasters worldwide as documented by scholars such as David Smolin (adoptive father and professor of law at Cumberland School of Law in Birmingham, Alabama) and others. Smolin popularized the phrase “child laundering” to describe how kidnapped and stolen children are passed off as “abandoned” by criminals who are paid “finder fees” by orphanages. In other cases, mothers are duped into believing their children are being sent to America or Europe for education and will return.

Placements are arranged first by agencies in their homeland and then onto American and European adoption agencies. All of this has led Smolin to call for a moratoria of international adoption (IA) until more regulations can be implemented to protect children and their families. Until that occurs, loosely regulated adoption policies will continue to put well-meaning individuals and couples at risk for unknowingly adopting children who were kidnapped, as happened to the Smolins. This horrifying discovery also happened to Rose Candis and to Timothy and Jennifer Monahan of Liberty Missouri and to Julia Rowlings who discovered her two daughters adopted from India had been sold.

Anther recently reported case is that of Mike Nyberg who adopted a little girl from Samoa:

“ . . . only to learn over time that her Samoan family had no intention of giving her up for adoption. The US adoption agency had told the Nybergs that their adoption would be closed, and that their little girl Elleia had been living in a foster home waiting for adoptive parents; but in Samoa, Elleia’s parents were told that their daughter could come to the US and receive a better education, and that the adoptive family would send money and regular updates on their daughter’s progress. The whole situation leaves the Nybergs trying to find their way through sticky moral territory.”

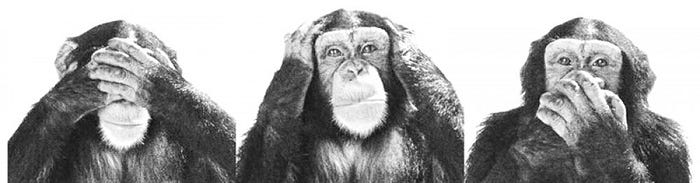

This may have likewise happened to Barrett without her knowledge. (See update at the end of this article about the agency barrett adopted through.) Should we turn a blind eye and a deaf ear to such serious consequences?

Such illegal and unethical practices led Guatemala, Ethiopia, China, and South Korea to cease or greatly limit their IA programs. The decision of these countries to discontinue the exportation of their children for adoption was also due to children from Russia and China, Ethiopia and Ukraine being rehomed — given by their “forever parents” to others without agency approval, vetting or home studies.

Russia stopped sending children to America for adoption because of the number of Russian adopted children abused (such as Mahsa Allen), abandoned (such as Artyom Savelyev who was put on an airplane back to Russia alone at 7 years of age), to numerous Russian adopted children sent to the Ranch for Kids, in Montana, to at least 17 Russian children who died in domestic-violence incidents in their American families.

Haiti’s poverty has made it an IA “hot spot” with an estimated that 3,000 children trafficked each year, many for adoption. Moreover, in January 2010, an earthquake in Haiti left hundreds of thousands of people dead, injured, and displaced, and over a million homeless. This tragedy triggered a stunning — albeit not uncommon — example of major child trafficking for adoption: A scandal involving missionaries swooping in and hurriedly scooping up children, many of whom were not orphans but had families. Ten missionary members a group, known as the New Life Children’s Refuge, did not have proper authorization for transporting the children out of the country and were arrested on kidnapping charges. NLCR founder Laura Silsby was found guilty and sentenced to time served in jail prior to the trial.

The fact that one of Barrett’s children was reportedly adopted from Haiti in the aftermath of the earthquake rightly set off alarms for those involved in adoption, personally and professionally. There is good reason to be apprehensive about the legitimacy of any adoption from that locale, especially at that exact time in history. Yet, the backlash against legitimate concerns has been fierce, as is often true of any criticism of adoption and/or adopters.

Ibram X. Kendi, is an award-winning historian and a New York Times best-selling author. He is Professor of History and International Relations and the Founding Director of the Anti-Racist Research and Policy Center at American University, and the Andrew W. Mellon Professor in the Humanities at Boston University, and the founding director of the BU Center for Antiracist Research.

Kendi recently spoke out in light of Amy Coney Barrett’s nomination, and the revelation that she had adopted two children from Haiti, one in 2010 in the aftermath of Haiti’s earthquake and has been vilified with condemnation and chastised for suggesting Barrett could be a “white colonizer” who uses her two adopted Haitian children as “props” and Tweeting:

“Some White colonizers ‘adopted’ Black children. They ‘civilized’ these ‘savage’ children in the ‘superior’ ways of White people, while using them as props in their lifelong pictures of denial, while cutting the biological parents of these children out of the picture of humanity.”

As a result, Kendi is facing calls for his termination of his University position. Yet, Kendi’s critical views of IA and transracial adoption are neither wrong nor unique, but rather are shared by many experts in the field. In light of all of the horribly tragic outcomes of many transnational adoptions, how irresponsible it would be not to have dire concerns? Yet we want to shoot the messenger?

To demonize his message or that of others — to castigate him or make him suffer consequences for speaking truth about a well-known reality, albeit one we’d rather not admit — is akin to firing a whistleblower.

Transracial Adoption: Long-Standing Controversy

“International adoption, the movement of predominantly non-white children from the postcolonial, so-called Third World to white adoptive parents in Western Europe, North America, Australia and Scandinavia, was born in the chaotic aftermath of the catastrophic and genocide-like Korean War. This forced child migration, which today involves around 30,000 children annually, has seen the trafficking of an estimated half a million children to date.”

Ruth Ben-Ghiat, a New York University professor of Italian and history Tweeted in support of Kendi’s comments:

“Many authoritarians seized children of color for adoption by White Christians. Pinochet’s regime did this with indigenous kids and Nazis took Aryan looking Poles for German families. Trump takes migrant kids for adoption by Evangelicals.”

Transracial adoption has long evoked intense debate. On one side are those who believe that finding homes for children in need is greater than ethnic differences. On the other side are those who believe that adoptive placements should not strip children of their racial identity and to do so is — especially transnationally –colonialism and imperialism. Paula Fitzgibbons, white mother of three, two of whom were adopted from Haiti, says: “The most blatantly racist people I have personally known are white parents who adopted black children.”

This claim cannot be ignored in cases such as that of Kenny Kelly Fry, of Osceola, Iowa, who were found guilty in 2019 of two counts each of child endangerment, for abuse including food depravation causing malnutrition and the neglect of two Black children: a 10-year-old girl and an 11-year-old boy adopted from Ghana years prior.

In 2018 transracial adoption made worldwide headlines when Sarah and Jennifer Hart who adopted six Black children domestically ended all eight of their lives by intentionally driving their vehicle off a cliff, seemingly to avoid abuse charges reported in 2008 and 2010 when they family lived in Minnesota including beatings with a belt and food depravation. Reports were again made in 2013 after the family moved to Oregon and yet again in 2017 while they resided in Washington state. All the while happy, smiling posed family photos were regularly posted online.

The hypocritical life of the Hart family eerily mirrors that of Myka Staufferwho “rehomed” (read abandoned) the son, Huxley, she and her husband had adopted from China. Stauffer made her living as a social media “influencer,” documenting the life of the adorable toddler and the rest of the “perfect” blonde-haired family on YouTube. Fans noticed seeing Huxley less in the Stauffer’s videos leading the glamorous mom to reveal that Huxley’s special needs which included autism became “too much” for her to handle and she found him another family better equipped which sparked internet outrage.

It is abhorrent behavior like this, as well as celebrities and politicians putting their transracial adopted children on public display, that leads to claims of adopted children being used as “props.”

Sherronda J. Brown (essayist, editor, and researcher who writes about culture and media through a Black feminist lens with historical and cultural context) examined the well-publicized Hart tragedy, taking a look at the backstory and larger implications, and wrote:

“This is why performative white allyship is so dangerous, and not just for the Black and non-Black kids who get adopted by them. It is insidious, to say the least, when ‘good white folks’ impersonate someone who truly cares about anti-racism work, even as they continue to uphold white supremacy in their words and actions, and continually harm people of color.”

Regarding a multitude of online photos of the Hart adopted children, Brown notes:

“We witness this ally theater daily, both in our communities and on the larger world’s stage. We see the way that people like the Hart couple insulate themselves with people of color as tokens and trophies to provide themselves an alibi for their racism. . .

“Their white saviorism complex is painfully obvious, a perpetuation of the colonialist and imperialist self-aggrandizing belief that people of color always need white people to save us, even from the white supremacy that they actively participate in and continually benefit from.”

Lemn Sissay comments on the concept color blindness, noting that it effectively renders those of color and their needs invisible. Transnational and transracial adoptees are taken, the disappear, and made invisible via homogenization and assimilation. Sissay quotes Mike Stein, in evidence presented to a British House of Commons select committee, by the Association of Black Social Workers and Allied Professionals:

“The most valuable resource of any ethnic group is its children. Nevertheless, black children are being taken from black families by the process of the law and being placed in white families. It is, in essence, ‘internal colonialism’ and a new form of the slave trade, but only black children are used.”

Haiti: Best intentions paving a road to disaster

Paula M. Fitzgibbons is an award-winning freelance writer (the New York Times, New York Magazine, Today’s Parent, and more) and former pastor in the Lutheran Church (ELCA). When she sought to adopt she was told by the director of a Haitian adoption agency that “Haitian children were generally godless and needed saving.” She and her husband were instructed not to let a Haitian child speak their native language and that their job as adoptive parents was to “beat the Haitian out of them,” right down to the size of rod to use and a website with detailed instructions.

The agency director warned the Fitzgibbonses that “our children might worship Satan. She described . . . as future criminals and sluts — unless we molded them into upstanding, God-fearing, born again, Jesus-loving Americans. She described their parents in the same way, repeatedly calling them liars and beggars.”

On online message boards, yahoo groups, and adoption “camps” Fitzgibbons sought help and support from, she found many believed the behavioral issues they saw in their Haitian adopted children were “because they had not yet been fully stripped of their cultural identities” and at least one comment that “the earthquake of 2010 was a welcome punishment from God for the evils of the Haitian culture. He hoped it would be a wake-up call for Haitians.”

All of this substantiates and validates Professor Kendi’s assessment of transracial as being colonialistic as spot on.

Fitzgibbons writes:

“The concept of transracial adoption is predicated upon the idea that we (the white adopters, in this case) have something that the parents of the children we are adopting lack. Most often, that thing is resources, a commodity we consider more important for happiness than familial closeness, culture, or community. More common than I’d ever imagined before entering the world of transracial adoption, though, is the belief that the thing white people have over people of color within the adoption triad is superiority in one or more areas: education, lifestyle, values, and the biggie in the community of people adopting from African and black Caribbean countries: salvation.

“In both cases, there exists a deprecating tone of white rescue — the new colonialism.

“The very belief that we should adopt in order to rescue those who we consider less-than is classist. When we pair that with the assumptions made about people because of the color of their skin, their culture, or what we think we know of their country, we land at the intersection of racism and classism, the epicenter of dysfunctional adoptions.”

Fitzgibbons notes the danger of adoption as salvation:

“This pervasive adoptive parenting theme, that one’s child needs saving, erodes both the parent-child bond and the child’s own sense of self. . . . Very little is more daunting to a child than the feeling that he is where he is because he needed to be saved. . . Immediately, from the moment of adoption then, she is confronted with her own ill-perceived inferiority. She is not worthy. Her race and culture, her very life story are less-than.”

The Real Experts

What happened in Haiti is a particularly glaring example of best intentions gone horribly wrong. In general, however, even when everything is perfectly legal in adoption, it doesn’t mean it’s ethical or devoid of corruption and exploitation.

More than academics and “professionals” or adoptive parents, the real “experts” on racial issues in adoption, are transracial adoptees. We need to hear what they have to say about their lived experiences — even if it is painful to hear — and not dismiss them as “disgruntled” or ungrateful.” As Nicole Chung, Korean-born, American-adopted author states: “Stories of transracial adoptees must be heard — even uncomfortable ones.”

Adoption is touted as being in the best interest of those who are adopted. But is it? You might think that adopted people are lucky or grateful. In fact, many express resentment at such expectations which downplay or ignore the losses they experience. Yet, until recently, the voices of those whose lives are shaped by these decisions have been left out of debates, discussions and policy-making, over shadowed by the money-makers and the paying clients in the mega-billion-dollar adoption industry.

How do adoptees feel about being adopted? Adoptee memoirs and blogs such as Lost Daughters, Dear Adoption, Adoptee in Recovery, Adoptees On, I Am Adopted, Adoptee Rights Law, describe feelings of loss, confusion, feelings of abandonment, rejection and sometimes anger. A small sampling of what some adoptees have to say, follows:

“We adoptees have a big hole where our family and heritage should be, so the idea is that we will consume to fill the hole, such things a cigarettes, food, booze, pharmaceutical drugs, etc. We will also have mental, emotional, and relational problems, which will land many of us in institutions and the court system with legal problems and divorces, etc. We will be money-makers not only for baby brokers, but for many industries and the government itself. Unhappy people are the best consumers.” Lisa Haemisegger Allis

“I am adopted also. Growing up, I could not imagine being anti-adoption. I did not even realize I could have negative feelings about being adopted, even though I did have those feelings, all the time.

“It’s hard to describe the disconnect I had from my feelings.

“When I found my family, at age 48, all the repressed feelings came flooding in. I finally realized that I did have a real mother, and an entire family that I was never allowed to know.” Jamie Smith, Facebook“We Adoptees are not Children, we’re Human Beings who spend a fraction of our lives as children and decades living with the brutal consequences of Relinquishment and Closed Adoption. Every cell in our bodies knows that we have another identity besides Adoption and longs to know it but we face barriers.” Nicole Burton

“I sat in a church service. The pastor asked what adoption meant. All the non-adopted people were giving answers like chosen. Special. Lucky. I finally could not take it anymore and raised my hand. My answer was “Disposable” you could have heard a pin drop.” Gina Johnson Miller, Facebook

“Being adopted is like living in a vacuum, creating oneself in one’s own image. But inside there is emptiness, and the emptiness feels like abandonment…. Adoption Contracts and the Adult Adoptee’s Right to Identity, Heidi A. Schneider

Those adopted across national borders additionally experience loss of heritage and culture and have little to no ability to know or ever meet their kin. Adopted people, writes Barbara Sumner, author, “come from nowhere. You are strange fruit of obscure origin. The lack of a bloodline marks you.”

Add to that the fact that many transnational adoptions are also transracial. For most, navigating all that entails is complex and daunting. Feeling empowered enough to speak and write about it takes courage for those expected to be quietly imbued with gratitude for having been rescued by zealous righteous “Christians” in order to increase the ranks and be a soldier of God. Others saviors in shining armor believe they are providing children a “better” with all its amenities, some influenced by celebrities — America’s trend setters. Over the last recent decades celebs such as Angelina Jolie, Madonna, and Sandra Bullock role-modelled transracial adoption — romanticizing and popularizing it — making it a badge of liberalism for some.

How do those adopted transnationally and/or transracially feel about their circumstances?

Angela Tucker is a nationally-recognized thought leader on transracial adoption and is an advocate for adoptee rights speaks for many transracial adoptees when she relates:

“Growing up, I often wondered why black parents didn’t adopt me. I wondered why white parents were always the ones adopting kids of color.”

Sunny J. Reed, transracial adoption writer/researcher, budding PhD student writes:

“[A}doption, the so-called #BraveLove, comes with a steep price; often, transracial adoptees grow up with significant challenges, partly due to the fact that their appearance breaks the racially-homogenous nuclear family mold. . .

“Racial identity crises are common among transracial adoptees: what’s in the mirror may not reflect which box you want to check. . . . Growing up, I’d forget about my Korean-ness until I’d pass a mirror or someone slanted their eyes down at me, reminding me that oh yeah, I’m not white.”

In the aftermath of World War II and Korean War, more than 200,000 Korean children were adopted by families abroad, making South Korea was the fourth largest provider of children to U.S. families, sending more than 1,600 orphans that year, according to the U.S. State Department. It is thus that Korean adoptees, being the first cohort of transnational and transracial adoptees to come of age, are the most vocal about their experiences.

Jane Jeong Trenka, an activist and award-winning author has written three books about her and others’ lives as transplanted adoptees. Trenka was adopted from Korea at the age of six months in 1972 an grew up in a rural Minnesota town where she never felt she belonged. She repatriated to South Korea in 2008 where she resides with her daughter and continues her activism, helping single Korean mothers fight the stigma that led to so many of them losing their children to adoption.

JS Lee is another Korean American author who writes about trauma, race, and adoption:

“Like many transracial adoptees with White parents, I was raised in racial isolation, which caused me to have a fractured identity, experiencing racial confusion and internal bias. When I looked in the mirror, the face I saw was not what I expected or wanted to see. I didn’t look like my parents and siblings, or my friends, or the people who I read about in books and saw in magazines and on television. I was often told race didn’t matter, despite the many racist jokes and slurs carelessly flung my way by family, schoolmates, and strangers.

“Some swore they forgot I was Asian and considered me to be White. The gaslighting and denial had me blaming myself for my own suffering.”

Mae Claire, who was born in Haiti and trafficked for adoption, knows the truth because it is her life:

“A typical adoptee is ripped from their environment and forced to survive with new expectations, new rules, new laws that govern their immediacy. They are forced to adapt….not the other way around.

“A typical adoptee of color is coming from a country that is deemed “poorer” and in need of saving. Poverty should NEVER be a good enough reason to take someone else’s child….and it should never be a reason to go the extra mile to falsify documents.

“When it comes to illegal and illicit adoptions, Haiti should get a gold star. . . .

“We become props.”

This is not political. Questioning is not criticizing. Nor is raising legitimate concerns “repulsive” or “attacking”. Questioning the Barretts’ — or anyone else’s — adoption(s) from post-earthquake Haiti, by Kendi or by anyone else, is totally appropriate, reasonable and needed to prevent future tragedies.

UPDATE, 10/19/20: It has been reported that the agency Amy C Barrett used to adopt her son was A New Arrival, which lost its accreditation in 2017. From the NY Times article reporting this: “Many children weren’t literal orphans.”

UPDATE. 10/24/20: Susan Silverman white transracial adoptive mother writes: “Kendi, who came under a barrage of criticism himself, clarified that he was not saying that all white parents of Black children are inherently racist, but that they are not, by definition, not-racist and that, in fact, racism has even been a motivator in transracial adoption by white parents of Black children.”

Silverman also says: “Barrett, sadly, has only furthered this dynamic, distinguishing between her biological and adopted children in a way that made me — also a parent through both birth and adoption, and also a white mother to two Black children — gasp.”

For more about the events that occurred in Haiti in 2010, see:

- After Haiti Quake, the Chaos of U.S. Adoption

- Child Trafficking and Adoption in Haiti

- Lost children: Why they should stay in Haiti

- Haiti: Numerous Mobs Attack Two Foreigners Believed to be Kidnapping Children for Adoption

- Tragedy Exploited: A Sad History Repeating Itself in Haiti

- Human Trafficking and the Haitian Abduction Attempt: Policy Analysis and Implications for Social Workers and NASW

- How to Protect Haiti’s “Orphans”

- Haiti: Officials Rescue and Return to Their Parents 50 Trafficked Children; 100 Others Await Rescue

For more about transnational and transracial adoption see:

· ICAV Perspective Paper: Illicit Intercountry Adoptions

· Dear Dad, You are Still Racist

Transracial Adoption Frequently Ruins Lives — I Say This As A White Adoptive Mom

· The Lie We Love — Foreign Policy

· The Intercountry Adoption Debate

· Code Switch: Transracial Adoptees On Their Racial Identity and Sense of Self

· The Personal is Political: Racial Identity and Racial Justice in Transracial Adoption

· Critics of Amy Coney Barrett and her adopted children are wrong. So are her defenders.

· Reverse Robinhoodism: Pitting Poor Against Aflfuent Women in the Adoption Industry

· The Parallels Between International Adoption and Slavery

· Intercountry adoption: Privilege, rights and social justice